The skies have always been a realm dominated by birds and insects, but nature has crafted other, more unexpected aviators. Among them, the flying lizard (Draco genus) stands out as a marvel of evolutionary adaptation. Unlike birds or bats, these creatures don’t rely on wings to stay aloft. Instead, they’ve perfected the art of gliding using an extraordinary structure: extendable ribs that support a thin, membranous patagium. This unique adaptation has captured the attention of biologists and engineers alike, offering insights into the aerodynamics of unconventional flight.

The Draco Lizard’s Gliding Mechanism: A Biological Marvel

Native to the forests of Southeast Asia, flying lizards have evolved a remarkable method of aerial locomotion. When grounded, they resemble typical small lizards, but when threatened or in search of prey, they leap from trees and unfurl their patagium—a stretchy membrane supported by elongated ribs. This sudden transformation turns them into living kites, capable of gliding distances up to 60 meters with surprising control. Unlike parachuting animals that descend passively, Draco lizards actively manipulate their membrane’s shape and tension, adjusting their trajectory mid-flight.

What makes their flight particularly intriguing is the efficiency of their design. The patagium isn’t just a flat sheet; its slightly curved profile generates lift, much like an aircraft wing. Researchers have observed that the lizards often angle their bodies to optimize airflow, reducing drag and extending glide range. This level of aerodynamic sophistication challenges traditional assumptions about vertebrate flight and raises questions about how such a lightweight, flexible structure can outperform rigid wings in certain scenarios.

Lessons for Biomimetic Design

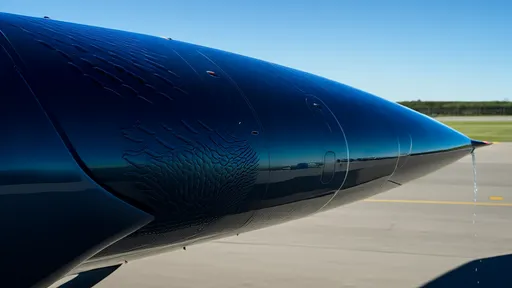

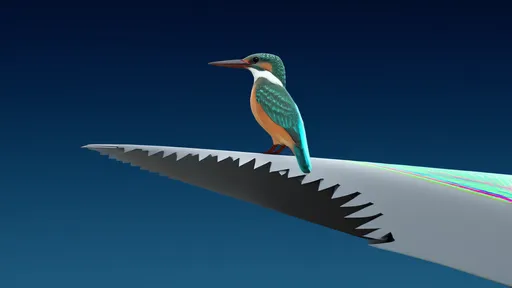

The aerospace and robotics industries are taking notes. Modern drones and gliders typically rely on fixed or flapping wings, but the Draco’s approach suggests an alternative: deployable, shape-shifting surfaces that balance flexibility and stability. Engineers speculate that mimicking the lizard’s rib-supported membrane could lead to drones capable of navigating tight spaces or adapting to sudden wind changes. One experimental prototype, inspired by the patagium, uses collapsible carbon-fiber rods and elastic polymer sheets to replicate the lizard’s on-demand wing deployment.

Beyond hardware, the lizard’s flight strategy offers software insights. By studying how Draco adjusts its posture mid-glide, researchers are refining algorithms for autonomous vehicles. For instance, subtle shifts in the lizard’s limb position alter airflow patterns, enabling precise landings on narrow tree trunks. Such micro-adjustments could revolutionize how small-scale drones handle turbulent environments or execute pinpoint deliveries in cluttered urban areas.

The Physics Behind the Patagium’s Efficiency

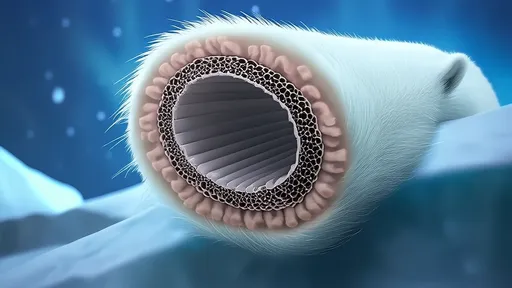

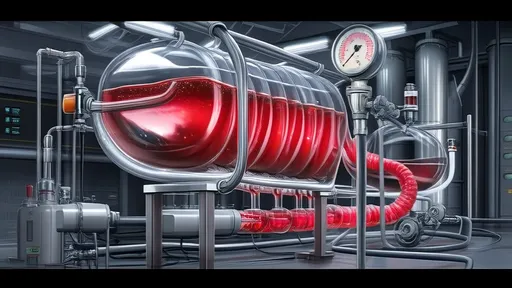

Aerodynamic analyses reveal why this system works so well. High-speed videography shows that the patagium’s leading edge remains taut during flight, while the trailing edge ripples slightly—a feature that may reduce vortex-induced drag. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models confirm that the membrane’s slight camber generates low-pressure zones above it, providing lift without excessive energy expenditure. This contrasts sharply with bird wings, which require constant flapping and muscular effort.

Moreover, the lizard’s ability to reconfigure its glide path by curling its tail or tilting its body hints at passive stability mechanisms. Unlike engineered gliders that need complex control systems, the Draco achieves agility through biomechanical feedback loops. For example, a downward gust might naturally stretch the patagium further, increasing lift momentarily without active intervention. Such passive stability is a gold standard in aerospace design, often sought after but rarely achieved with such elegance.

Evolutionary Trade-offs and Ecological Niche

Why did this form of gliding evolve in Draco lizards but not others? The answer lies in their arboreal lifestyle. Unlike true fliers, gliders don’t need to generate lift from a standstill; they capitalize on elevated launch points. For a small lizard living in dense canopies, the energy cost of developing muscle-powered wings would outweigh the benefits. Instead, the extendable rib system provides a lightweight, low-maintenance solution that fits their hit-and-run survival strategy.

Ecologically, this adaptation allows Draco lizards to exploit vertical space efficiently. They can escape predators, chase insects, or move between trees without descending to the forest floor—a dangerous territory for a 20-centimeter reptile. Interestingly, different Draco species exhibit subtle variations in patagium size and shape, likely reflecting adaptations to specific forest structures. Some excel in long-distance glides across open gaps, while others maneuver deftly through tangled branches.

Future Research and Unanswered Questions

Despite progress, mysteries remain. How do juvenile lizards, with proportionally larger patagia, achieve comparable glide ratios to adults? What neural pathways enable such rapid deployment and adjustment of the flight membrane? Ongoing studies using motion-capture technology and genetic sequencing aim to uncover these secrets. Meanwhile, material scientists are experimenting with bio-inspired composites that replicate the patagium’s dual properties of elasticity and tear resistance.

The flying lizard’s story is more than a curiosity—it’s a testament to nature’s ingenuity. As researchers decode its secrets, we may witness a new era of aviation technology where flexible, adaptive wings become the norm rather than the exception. From search-and-rescue drones to high-efficiency gliders, the lessons written in the Draco’s ribs could shape the future of human flight.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025